Writing a novel is no easy task. Oftentimes years of blood, sweat, and tears go into creating the perfect manuscript and so, in a way, they are their author’s babies. Sometimes those literary stories catch the attention of those in the movie industry and an adaptation is made. Whilst for many this process is a beautiful experience, directors translating their inner thoughts exactly as imagined, for others it can be a horrible nightmare. From miscasting, to changing key elements, the list of potential woes is endless. Here are some cautionary tales about authors that hated adaptations of their books.

Less Than Zero (1987)

Less Than Zero is the debut novel from author Bret Easton Ellis and tells the story of Clay, a rich college student who returns home for winter break and begins to reflect on their lifestyle and situation. Less Than Zero was immediately picked up for the movie treatment, but Ellis’ expectations were not met.

Ellis resented the movie adaptation so much that he used the book’s sequel, Imperial Bedrooms, to take a pop at it. The book, written twenty-five years after the movie’s release, opens with the characters trashing a film that had been made about them.

Mary Poppins (1964)

Watching Mary Poppins is a staple part of most childhoods. The story of the super-cheery magical singing nanny has enchanted audiences and book readers alike for generations, and despite being almost sixty years old, continually manages to find new fans.

The Disney movie blended animated elements with live-action and whilst audiences loved this fusion, author P. L. Travers hated it. Travers was so displeased that stories tell how she openly wept during the premiere. After this experience, Travers refused to let Disney adapt any more of her books.

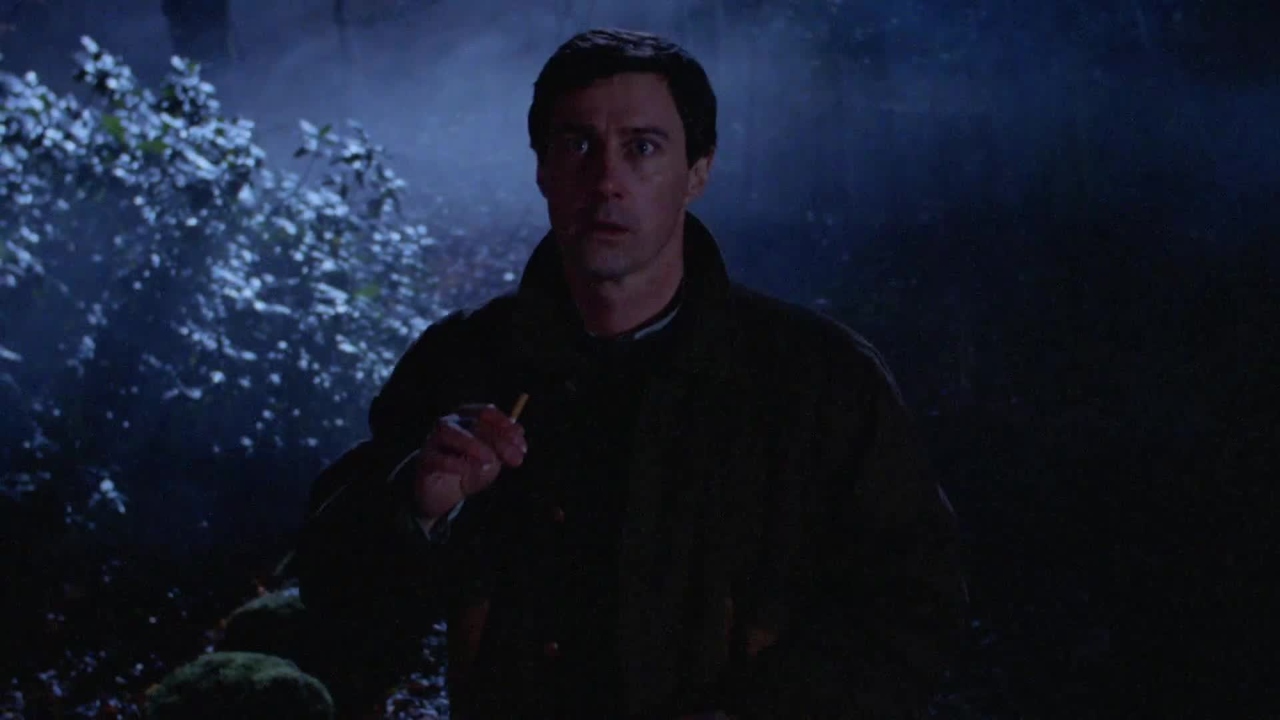

The Shining (1980)

One of the most famous examples of an author disliking the adaptation of their text is Stephen King and his novel The Shining. Initially King was delighted that famed director Stanley Kubrick would be overseeing the film, but upon viewing the finished product, found himself very disappointed.

King’s biggest issue was that, in his eyes, Kubrick made The Shining a domestic tragedy with its supernatural elements muted. King also disagreed with actor Jack Nicholson’s performance, believing that Jack Torrance didn’t have enough of an evolution as Nicholson was too eccentric from the start.

The NeverEnding Story (1984)

The NeverEnding Story is one of the most traumatic family films committed to celluloid, with some still unable to see horses anywhere near mud without getting heart palpitations. The 1984 movie joins troubled young boy Bastian who disappears within the pages of a mysterious book, to a bizarre fantasy world.

Wolfgang Petersen’s 1984 classic was adapted from a book by Michael Ende, but sadly the author was not as impressed by it as audiences. Ende called the adaptation ‘revolting’ at a German press conference. He hated it so much that he requested his name be removed from the credits.

A Clockwork Orange (1971)

Author Anthony Burgess was so upset about A Clockwork Orange that he came to regret having written the novel at all. He believed that the film made it easier for readers of the book to misunderstand what it was about. As such, Burgess feared that this misunderstanding would follow him forever.

Although the source material contained shocking moments, the impact was far greater when on screen and A Clockwork Orange caused controversy. During this time, Burgess came under constant attack for its creation, with little backing or support from the film’s director, Stanley Kubrick.

A Wrinkle in Time (2003)

In 2003, before the 2018 adaptation, came the first on-screen outing for Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time. The made-for-TV film tried to capture the magical and mysterious nature of the source, but was met with middling reviews from critics and viewers.

When L’Engle was asked about the film in an interview with Newsweek, she delivered a fairly damaging remark. When asked if she had seen it, she replied that she had ‘glimpsed’ it. When pushed about whether it met her expectations she replied, “Oh, yes. I expected it to be bad, and it is.”

From Hell (2001)

It isn’t just books that get the movie adaptation treatment, comic books and graphic novels do too. One of the graphic novel creators with the most adaptations of his work, is Alan Moore. Whereas Moore doesn’t mind Watchmen, he has struggled with screen versions of some of his other projects, with From Hell being the first to cause him problems.

The film, and source material, are set in Victorian London and follow a clairvoyant police detective as he investigates the infamous Jack the Ripper. Of the film, Moore damned it as an “absinthe-swilling dandy” and has admitted he only sold the rights because he never thought it would actually get made.

Jaws (1975)

It was with his 1975 movie Jaws that director Steven Spielberg broke into the big leagues. The story of Chief Brody’s hunt to stop a shark plaguing his small town had the world gripped, frightening an entire generation off of the ocean.

Jaws was in fact based on Peter Benchley’s novel of the same name. Whilst much of the adaptation is true to the source material, the ending is notably different. The change in direction displeased Benchley greatly. In fact, he was so angry that he was removed from the film’s set.

Tales From Earthsea (2006)

Ursula Le Guin has a long history with people trying to adapt her work. The first of which, made by Sy-Fy Channel, she absolutely hated. Amongst myriad problems, Le Guin’s primary concern was how the adaptation white-washed all her characters.

In 2006 Studio Ghibli attempted to convert Le Guin’s text. She was disappointed that Hayao Miyazaki would not be at the helm and that it would be his son Gorō Miyazaki instead. After viewing, she agreed it was a good movie, but it was not hers and was again troubled by the representation of race in the film.

Valley of the Dolls (1967)

Directed by Mark Robson, Valley of the Dolls was based on Jacqueline Susann’s novel of the same name. The story was inspired by Susann’s own experiences as a hopeful Hollywood starlet and followed three women as they struggled to make it as stars. Rather than walk red carpets, the women turn to barbiturates to cope.

The premiere of Valley of the Dolls was a lavish affair, and was held on a cruise ship. Susann was present and was not impressed with the film’s change of time period and ending. She went so far as to call it “a piece of s***,” to those in attendance.

Cool Hand Luke (1967)

American author and journalist Donn Pearce’s experience creating Cool Hand Luke was not a pleasant one. First, Pearce was hired to adapt the screenplay of his novel, but he was later replaced by a more experienced screenwriter. Then, on his last day on set, Pearce punched somebody.

Cool Hand Luke was very personal to Pearce, having been inspired by the two years he spent in a prison road gang. However, what really frustrated him was the now iconic line, “What we’ve got here is a failure to communicate.” Pearce believed the guards to be lacking the intellect to coin such a sophisticated phrase.

I Know What You Did Last Summer (1997)

Coming in the wake of the popularity of Scream, I Know What You Did Last Summer enchanted teenage horror fans. What few knew though is that rather than being inspired by Scream, the origin of the story came from Lois Duncan.

Duncan’s original novel was more of a suspense story mixed with melodrama, and she had hoped that any film adaptation would stay close to its tone. However, Duncan was horrified to discover that it had been re-worked as a slasher movie.

Timeline (2003)

After the success of Jurassic Park studios were lining up around the block to adapt the works of author Michael Crichton. For a while, Crichton was happy to oblige and there were a slew of adaptations of his works released into cinemas.

Then in 2003, came the film Timeline. The film, which starred Paul Walker and Gerard Butler, follows a group of archaeological students who became trapped in the past after travelling back in time to retrieve their professor. Crichton disliked the film so much that he refused to licence any further movie ventures.

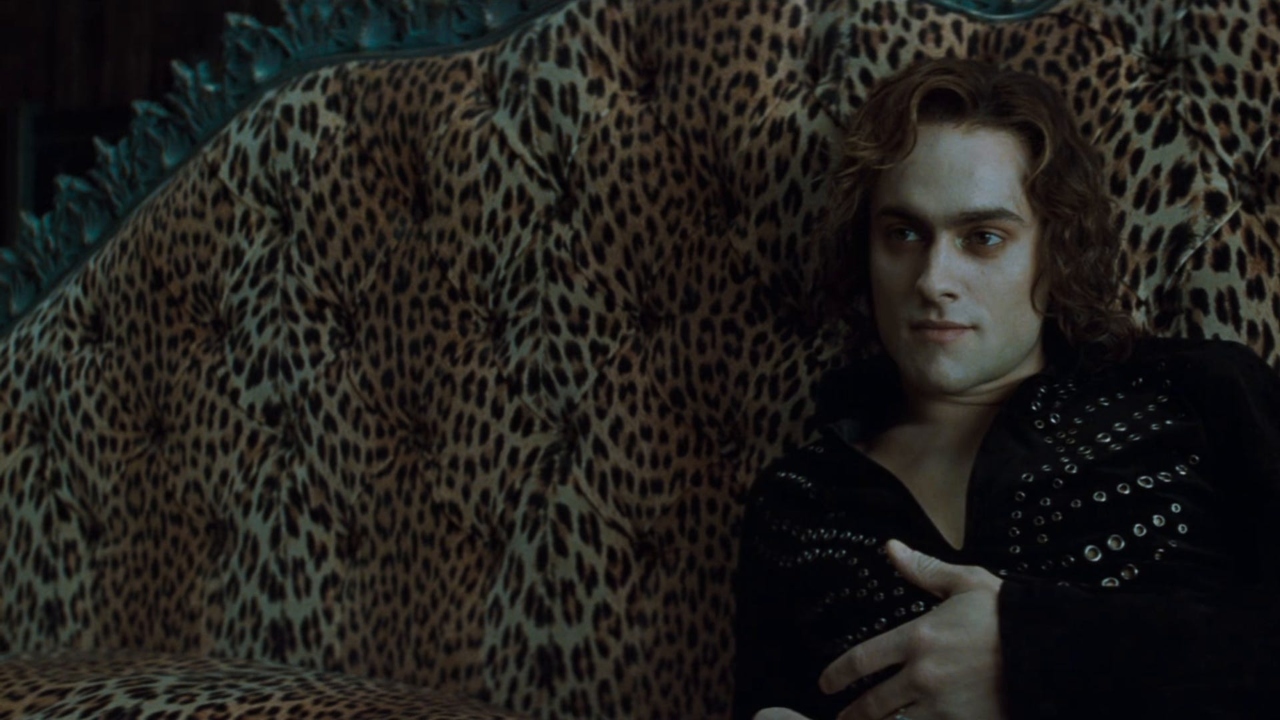

Queen of the Damned (2002)

Initially Anne Rice was horrified about the idea of Tom Cruise playing the role of vampire Lestat in the film Interview with the Vampire, but loved him when she eventually saw the film. This experience made her more open with the next adaptation, Queen of the Damned.

Sadly, Cruise was unable to commit to another turn as Lestat and so the studio hired Stuart Townsend. Then the film mixed elements of Queen of the Damned with the other Vampire Chronicles story, The Vampire Lestat. The result was a muddled mess. Rice has since disowned the film, claiming it “mutilated” her work.

American Psycho (1999)

After being upset with the adaptation of his debut novel Less Than Zero, it’s a surprise that Bret Easton Ellis let anyone near his work again. But in 1999 he agreed to let Mary Lambert loose with his most well known story, American Psycho.

Quite why he let the adaptation happen is unclear as Ellis’ main critique is that he believes the book didn’t need to be turned into a movie. He preferred the ambiguity that the book presented about Patrick Bateman’s actions, claiming that as vague as the film is, by showing anything, it confirms something.

Rawhead Rex (1986)

Whilst many believe that the first adaptation of Clive Barker’s writing was Hellraiser, it was actually a film called Rawhead Rex. Barker himself wrote the screenplay, keeping it very faithful to his original short story. However, he disapproved of the execution.

Upon viewing the film, Barker was not happy with how monster heavy the story had become. He also critiqued the quality and validity of the acting. Barker did learn from the experience though and his dissatisfaction compelled him to direct Hellraiser himself. The result being one of the best adaptations of a work of fiction.

V for Vendetta (2005)

Set in a future British totalitarian society, V for Vendetta stars Hugo Weaving as a shadowy freedom fighter, known only by the alias of V. The eloquent V intends to overthrow the government, but has to enlist the help of Natalie Portman’s Evey.

V for Vendetta has a passionate fan-base, however, the author of the graphic novel on which it is based, Alan Moore, is not one of them. The adaptation frustrated Moore with him calling the film a “Bush-era parable by people too timid to set a political satire in their own country.”

Das Boot (1981)

Before causing strife for author Michael Ende with 1984’s The NeverEnding Story, director Wolfgang Petersen destroyed another writer’s vision in 1981 with Das Boot. The source novel was written by Lothar-Günther Buchheim and was inspired by his time being part of a WWII propaganda video unit photographing U-boats.

Novelist Buchheim was so unhappy with the film version of Das Boot that he wrote an entire essay about his gripes. His main issue was that it was a “nasty falsification” of his novel. He argued that the American movie was merely a “cheap” and “shallow” action movie.

Forrest Gump (1994)

The film adaptation of Forrest Gump swept awards season, but there was one person missing from all of those winning speeches – author Winston Groom. Forrest Gump scooped six Academy Awards, but not one person thanked Groom for creating the story in the first place.

It wasn’t just that omission at the awards ceremony that riled up Groom. The author was also promised 3% net profits from the film, which he never received. His anger evidently lasted for a while, famously opening Forrest Gump’s sequel, Gump & Co., with words of wisdom advising “Don’t never let nobody make a movie of your life’s story.”

Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001)

Sometimes adaptations of books don’t happen until long after the author has passed away. In these instances it is the family estate that directors have to be mindful of. Sometimes these groups can be trickier to please than the original writers. One such person to find this out the hard way is Peter Jackson.

Whilst the world adored Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy, author J.R.R. Tolkien’s sons were not happy. Christopher Tolkien said, “they eviscerated the book by making it an action movie for young people aged 15 to 25.” He also lamented how his father’s art had been devoured by its own popularity.

Percy Jackson and the Lightning Thief (2010)

After the end of the Harry Potter series, studios were desperate to find the next big thing for kids and tweens. Rick Riordan’s Percy Jackson was one of the first contenders. Two films were released – Percy Jackson and the Lightning Thief and Percy Jackson: Sea of Monsters – though neither performed hugely well.

Despite having not actually watched either film, Riordan is disappointed with the adaptations. Reading the scripts was difficult enough for Riordan and he tried to fight against several aspects, such as ageing up the characters, but was overruled. Disney+ has a new adaptation in the works, which the author hopes will be more faithful.

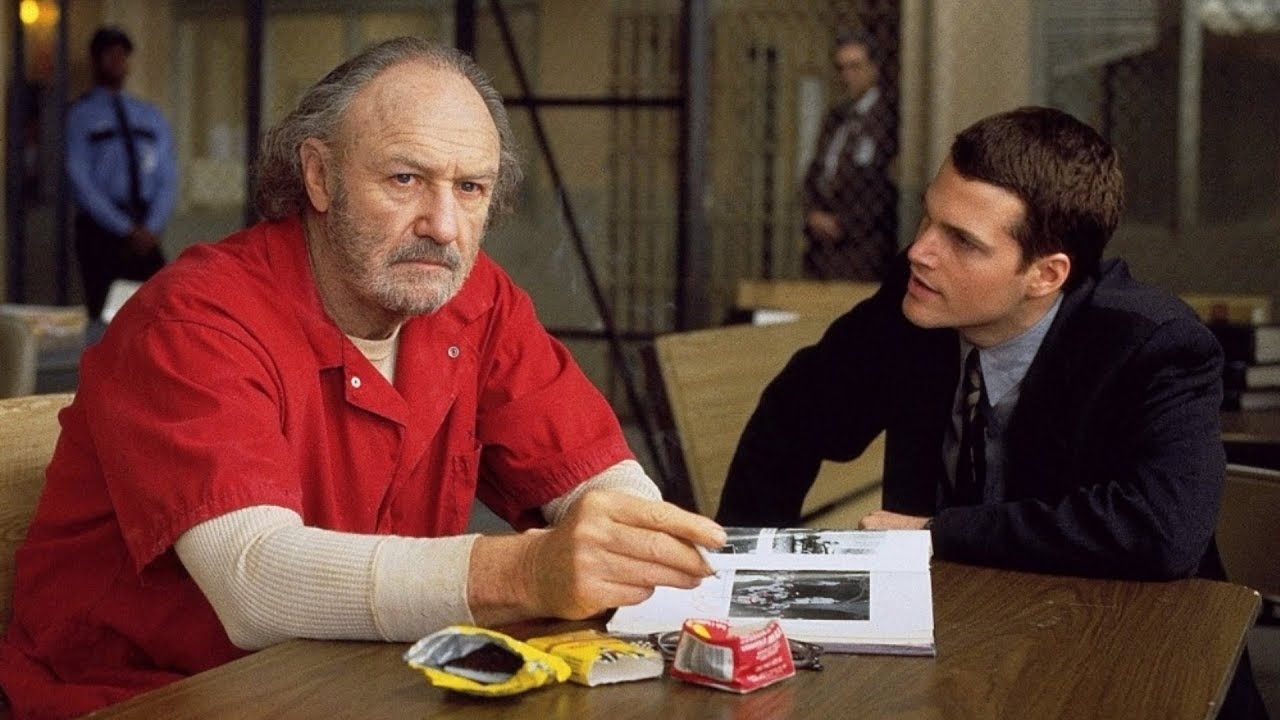

The Chamber (1996)

John Grisham’s literary works have been adapted many times over the years, and whilst the author is usually pretty happy with his films, there is one that he thinks less highly of. The bad penny amongst the crowd of good ones is 1996’s The Chamber.

After watching The Chamber, Grisham described it as a “train wreck.” The only positive he had was that Gene Hackman was the only good thing in it, but blames himself for selling the rights before he had finished writing it.

Solaris (1972)

Stanislaw Lem wrote the novel Solaris, which has been adapted not once, but twice. Lem has gone on record to say he didn’t really care for either of the adaptations, though it was Andrei Tarkovsky’s version in 1972 that led Lem to write about his despair.

He lamented his disappointment of not getting to see the titular planet of his story. Then he discussed how Tarkovsky had technically made a film more like Crime and Punishment than his own story. His reaction was somewhat strange as later on he wrote that he had only watched twenty minutes of the movie.

Sahara (2005)

2005’s Sahara, which starred Matthew McConaughey and Penélope Cruz, was a box-office disaster. From a $160 million budget, Sahara only recouped $68 million. The film was based on Clive Clusser’s Dirk Pitt stories, a character Clusser is very passionate about.

After Sahara tanked, Cussler believed the failure was due to him not being given the total script control he had initially been promised. Clusser tried to sue the production for $38 million, but lost, and ended up having to pay $13.9 million to cover the cost of the production’s legal fees.

My Foolish Heart (1949)

J.D Salinger is a literary hero of a generation. His stories, particularly Catcher in the Rye, captured the alienation felt by the youth at the time, and with coming-of-age dramas a solid part of the film landscape, many are surprised it hasn’t been given a big screen outing.

The reason for this is that Salinger has had his fingers burned by the film My Foolish Heart, a feature adaptation of his short story, Uncle Wiggly. Salinger was mortified by the ‘swooning’ and exaggerated love story so much that he swore to never let anyone else adapt his work again, lest they also butcher it.

Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory (1971)

Whilst a generation grew up enamoured with the film version of Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, author Roald Dahl hated it. In his own words he found the adaptation of his children’s novel, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, “crummy.”

Dahl also disagreed with the performance by Gene Wilder, who he described as “pretentious”, and said that director Mel Stuart had “no talent of flair.” Despite the film’s success, Dahl refused to release the rights for the book’s sequel, the author wary that history might repeat itself.

Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961)

Iconic actress Audrey Hepburn is synonymous with her film Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Hepburn made the role so intrinsically hers that it’s hard to imagine anyone else in the part, but the author of the novel on which the film is based, Truman Capote, had someone else in mind.

For Capote, his favourite literary creation belonged to one person only – Marilyn Monroe. Capote petitioned hard for her casting and was furious when Hepburn was chosen instead. The writer spent the rest of his life trashing the film for its miscasting to anyone who would listen.

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975)

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest author Ken Kesey was upset with the film adaptation from the early days of its production. Kesey was originally meant to be an active part of the production process, but left after only two weeks.

His reason for leaving was that he was very unhappy with the narrative direction the film was going in. Namely, getting rid of the viewpoint of Chief Bromden. Even after the film swept the Academy Awards, Kesey was so enraged that he refused to watch it.

The Last Man on Earth (1964)

Richard Matheson’s book, I Am Legend, has been adapted several times over the years. I Am Legend, starring Will Smith, is the most recent, and Omega Man, starring Charlton Heston the one before that. The original adaptation was 1964’s The Last Man on Earth, starring Vincent Price.

Not only do the three films share the same source material, they all annoy Matheson. Speaking on the book’s various adaptations, Matheson has said, “I don’t know why Hollywood is fascinated by my book when they never care to film it as I wrote it.”

The Cat in the Hat (2003)

Ever wondered why all the modern Dr. Seuss adaptations are animated? Well that is because it was a request of Dr. Seuss’ widow, the late Audrey Geisel, after witnessing the abomination that is the live-action version of The Cat in the Hat.

After reviewing the script for The Cat in the Hat, Geisel was horrified with the excessive potty humor and rude jokes. Upon release, she was so appalled with the final product she decided to reject any future live-action adaptations, and so all since have been strictly animation only.

Death Wish (1974)

The Death Wish series of movies is renowned for its violence, with film after film allowing Charles Bronson to hack his way through the bad guys. The first Death Wish was based on Brian Garfield’s novel of the same name, and whilst initially keen on the adaptation, he quickly changed his mind.

Problems began when a new producer overhauled the screenplay that Garfield had approved of. This new version glorified the very violence that Garfield’s novel was trying to prevent. The point of his novel was to prove that being a vigilante solves nothing, whereas Death Wish advocated it.

The Informers (2008)

With the exception of The Rules of Attraction, writer Bret Easton Ellis has had a tumultuous relationship with adaptations of his work. The latest to offend the author is 2008’s The Informers, which charts a week in Los Angeles in the year 1983.

What makes Ellis’ disdain for The Informers interesting is that he himself served as a writer on the project. Speaking about the failure, Ellis has said that “the movie doesn’t work for a lot of reasons, but I don’t think any of those reasons are my fault.”

Charlotte’s Web (1973)

The crux of E.B. White’s classic children’s book is that, however sad it is, Charlotte has to die. Her death is needed for that emotional punch that has devastated legions of kids. However, when animation house Hanna-Barbera wanted to cut it, fearing it was too dark, White fought tooth and nail to keep it in, and ultimately won.

Though he won that battle, in his eyes, he lost the war. White was abysmally disappointed by the film, particularly the frequent plot interruptions for “saccharine musical numbers.” His ultimate verdict was that the film of Charlotte’s Web was a “travesty.”

Patriot Games (1992)

The cinematic version of Patriot Games stars Harrison Ford as CIA analyst Jack Ryan, who after interfering with an IRA assassination, becomes the target of a renegade faction, led by Sean Bean, who are out for revenge.

Jack Ryan was created by author Tom Clancy, and whilst Clancy was happy to be a part of some of the other adaptations of his work, he immediately passed on Patriot Games. He didn’t give the production much of a chance, disassociating himself from the project after reading the first draft of the script.

The Alphabet Murders (1965)

Agatha Christie is responsible for some of literature’s best super sleuth detectives, including Miss Marple and Hercule Poirot. Christie’s novels have been adapted for screens since she began writing, but sadly she was often disappointed with the end result. So much so that she ended up regretting selling the rights to MGM.

Christie was quite vocal about her horror of Margaret Rutherford’s depiction of Miss Marple, which made her feel “sick” and “ashamed.” Her closest friends ended up banning her from watching 1965’s The Alphabet Murders with Christie sharing, “my friends and publishers told me the agony would be too great.”

Eragon (2006)

During an Ask Me Anything thread on Reddit, Christopher Paolini, author of the Eragon series, shared his views on the film version of his work. During the question and answer session he revealed, “the movie was… an experience. The studio and the director had one vision for the story. I had another”

Paolini is at least pragmatic about the adaptation though, and has found a silver-lining in his disappointment. The movie helped promote the book and Paolini is happy that the film at least introduced a “ton of new readers” to the series.

Simon Birch (1998)

Author John Irving always doubted that his novel, A Prayer for Owen Meany, could be adapted well for the screen. He was so reticent that he sold the rights with caveat that the films must have a different name, offering producer’s the alternate title of Simon Birch.

Sadly for Irving, his fears about his story translating from the page to screen proved true, especially when director Mark Steven Johnson deviated from the source material. Irving was so upset that he removed himself from the project entirely. With the differing titles, and Irving’s name not featured, he was able to distance himself very effectively.

The Handmaid’s Tale (1990)

The adaptation of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale may be a successful television series, but Atwood has had issues with the show since it progressed from its first season. However, the Hulu show is not the first time the book has made it onto the screen.

In 1990 there was another version, which starred Natasha Richardson. Atwood was vocal about her misgivings and criticized the film for its “lack of narration.” Atwood believed this to be a missed opportunity and vowed it would not be repeated; the series uses Offred as a narrator.

Hideaway (1995)

Hideaway is one of Dean Koontz’s best stories. The plot sees family man Hatch who, after being resuscitated after a car accident, develops a psychic bond with a serial killer who worships Satan. The film version saw Jeff Goldblum play Hatch, Alicia Silverstone his daughter, and Jeremy Sisto as the killer, and it was pretty fun.

Koontz however, did not see the appeal of the movie. He actively detested the manner in which the narrative was constructed, fearing that it presented the story in too confusing a way. Koontz also felt the palpable dread that permeated the novel had been lost.

Billy Bathgate (1991)

Billy Bathgate is one of Hollywood’s biggest failures, and thankfully for writer E.L. Doctorow has been lost from the public consciousness. Doctorow’s original book was a biographical gangster story that came runner-up for the 1990 Pulitzer Prize. With such established source material, the film should have been an instant win.

Disappointingly, during the adaptation process, writer Tom Stoppard made some big changes from Doctorow’s novel, inadvertently ruining what could have been an awards contender. The final cut of Billy Bathgate deviated so far from what Doctorow had originally written that he distanced himself from the project entirely.