Samurai were completely unafraid of death

Samurai were renowned for their fearlessness in battle, as they embraced the idea of a glorious death rather than a humiliating injury or defeat. In particular, dying in battle for the emperor or a military leader was a great honour: your family would be famous for generations after your death.

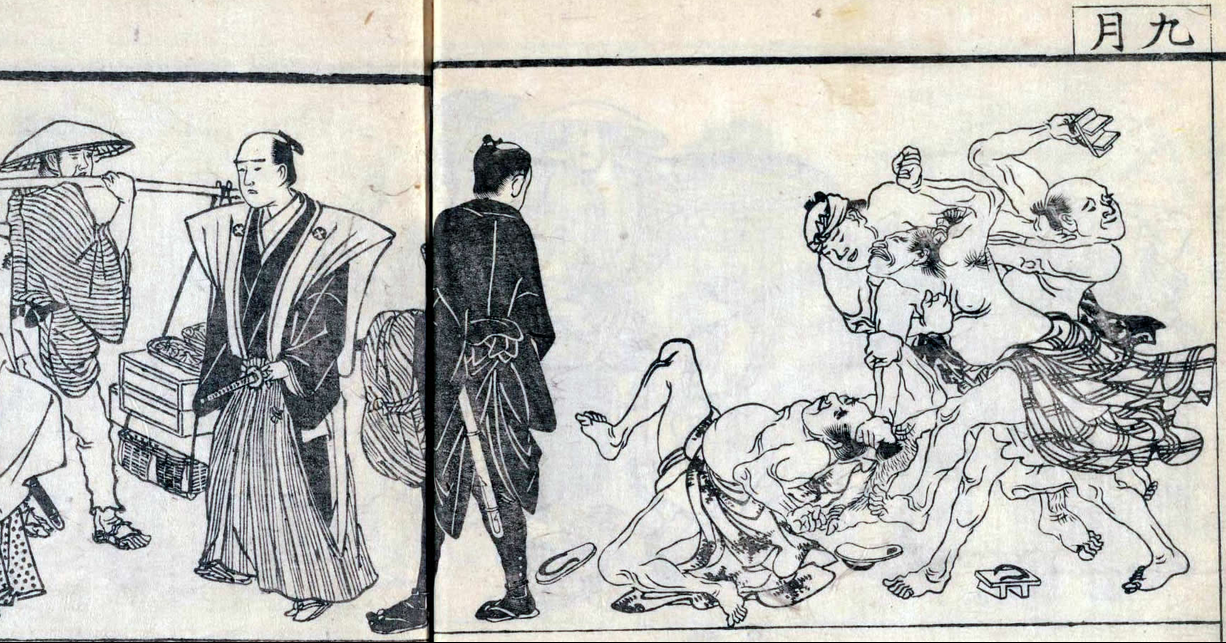

Disrespect from peasants was punishable by death

Kiri-sute gomen, or ‘the right to cut and leave [a victim’s body]’ was a permission granted to the samurai classes to kill any lower-class person on the spot for disrespecting them. Such a strike had to take place immediately after the insult, which included behaviours like pushing, shoving and cutting in front of the samurai.

They tested new swords on hapless passers-by

Tsujigiri, meaning ‘crossroads killing’, was the practice of testing out a new sword in a particularly grisly manner. The samurai would take their new katana into the streets, typically at night time, and attempt to murder a defenceless passer-by. Tsujigiri was banned by the Edo government in 1602.

They obeyed the warrior code of Bushido

Under the code of Bushido, which varied greatly between eras, samurai learned the importance of studying, self-discipline and self-sacrifice. One lord wrote: “If a man does not investigate into the matter of Bushido daily, it will be difficult for him to die a brave and manly death. Thus it is essential to engrave this business of the warrior into one’s mind well.”

They were trained from childhood in martial arts

Children of the samurai classes began their training at an early age. They studied the sword, bow and arrow, the spear, the halberd and even firearms. Horseback riding was a prerequisite for a life on the battlefield, and samurai children were taught to cope in all types of terrain, hence swimming and diving were also part of their education.

They fought alongside women

The wives and daughters of the samurai had very little power, as they were mostly left to household duties and ordered into political matches. However, the samurai did fight alongside women, known as Onna-musha. As part of the Bushi warrior class, Onna-musha were highly trained in weaponry and warfare. Among their numbers were the famous fighters Tomoe Gozen and Hangaku Gozen.

Tea-drinking and poetry were hallmarks of the samurai

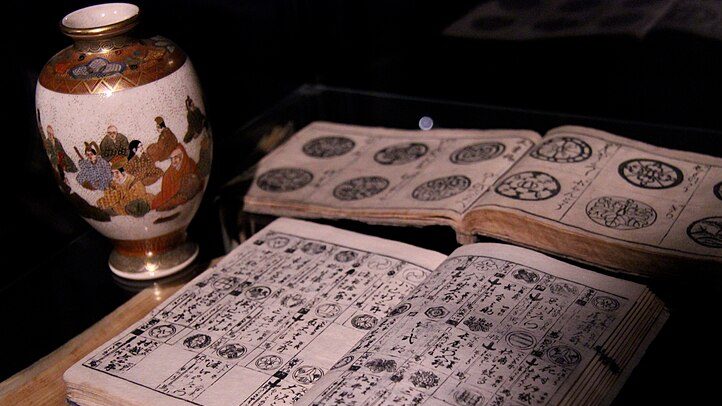

The samurai borrowed heavily from other cultures to build a refined set of artistic and literary practices. They engaged in tea ceremonies, ink painting, writing poetry and gardening, inspired by the arts of medieval China and Zen Buddhist monks. Some samurai built extensive libraries full of literature about warfare and religion.

Samurai could switch allegiances

Despite strict codes of loyalty and fealty, it was not unusual for samurai to change their allegiances many times over a lifetime. In fact, samurai’s self-chosen names often reflected where their loyalties lay, and one samurai might go by many different names over time as their priorities changed.

Decapitated enemy heads were a noble trophy

After a battle, samurai would collect the severed heads of their enemies and take them home as a trophy. The heads were then diligently cleaned, their hair was brushed and their teeth were blackened with an iron filing mixture. White teeth were a mark of quality, so this teeth-blackening practice was a way to disgrace the enemy.

Samurai left the life to become businessmen

The government stopped funding samurai in the late 1800s and the class was gradually abolished. However, samurai still made up five percent of the Japanese population. As these families broke away from medieval feudal customs, they entered a wide range of prestigious professions. By 1920, 35% of former samurai class members were working as businessmen.

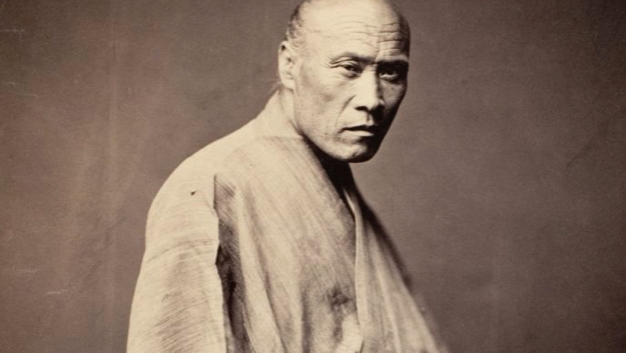

They were their own social class

The word Samurai originally meant, “those who serve in close attendance to the nobility,” but over time it became more associated with middle and upper class warriors. During the early part of the Tokugawa period, the Samurai became a closed social caste, containing around ten percent of the Japanese population.

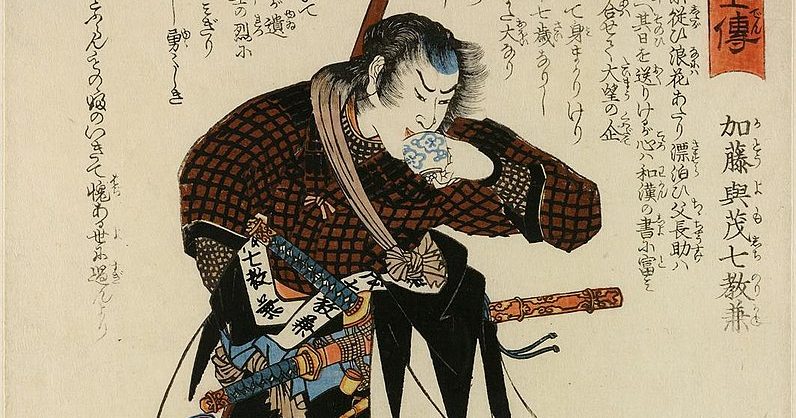

Their swords were extremely important to them

The katana, more commonly known as a Samurai sword, is one of the most iconic weapons ever. Samurai also carried a smaller blade, with the pair of weapons – referred to as a ‘daisho’ – one of the distinctive symbols of the Samurai class. The Bushido code stated that a samurai warrior’s soul resided in his katana, and the swords were exquisitely cared for and given names.

They used a number of weapons

Although the katana is the weapon most associated with the samurai, they also fought with a number of other armaments. Samurai warriors would frequently fight with longbows called ‘yumis’ and spears called ‘yaris.’ They would practise religiously with these weapons, making them fearsome combatants at any distance.

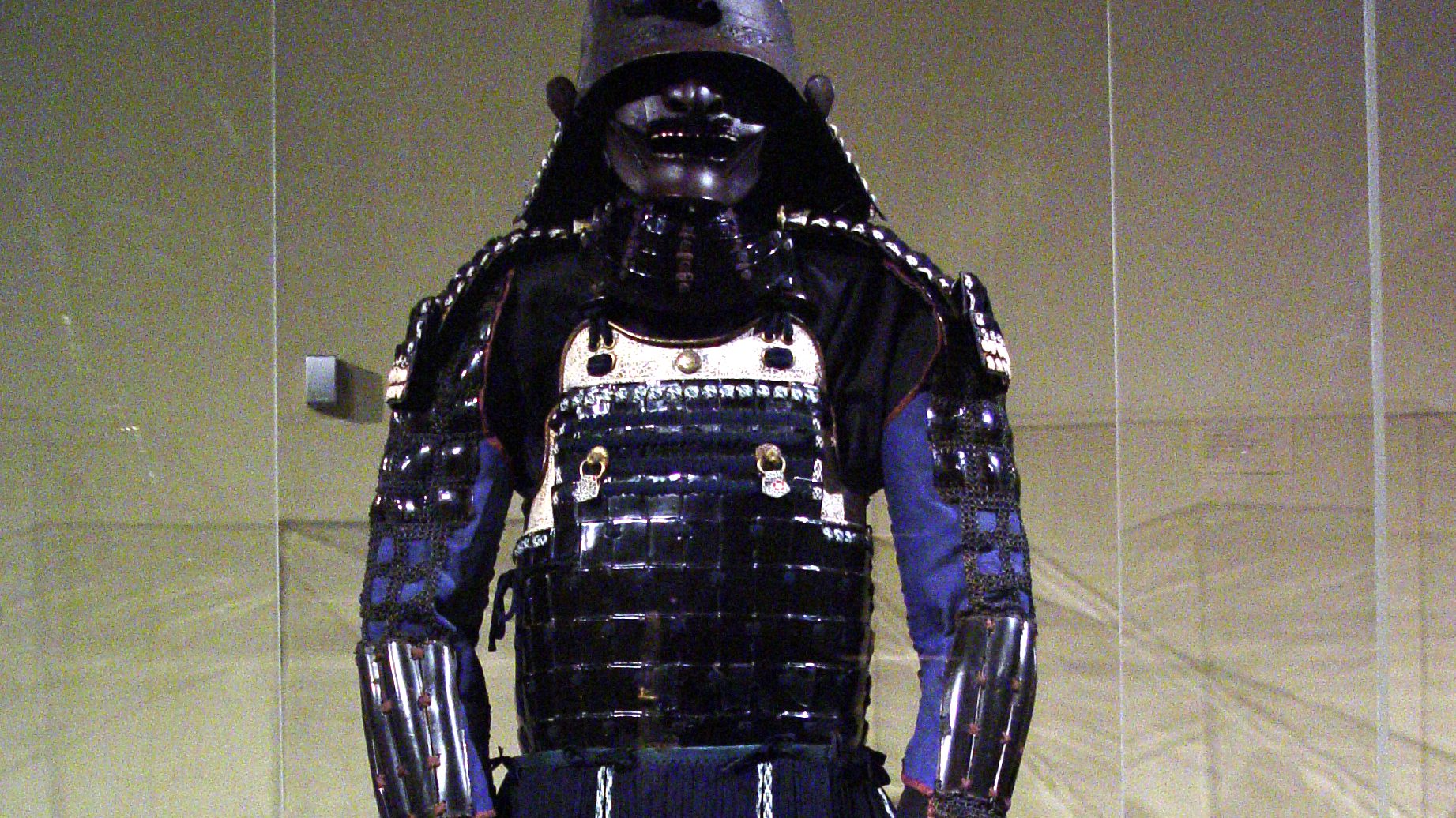

Their armour allowed for great flexibility

Unlike the armour worn by European knights which sacrificed mobility in favour of greater protection, samurai armour was designed to allow its wearer to move quickly and easily. This was achieved by using lacquered plates of either metal or leather, bound together with silk laces. Lightweight armour of this kind allowed for the skilful, agile style of combat that the samurai were famous for.

They wore masks to intimidate their enemies

In addition to a helmet (known as a ‘kabuto’) which was constructed out of riveted metal plates, many samurai also wore masks that covered the lower half of their face. These would often sport terrifying demonic features such as tusks or jutting fangs, serving to both protect the samurai and intimidate their opponents.

They were highly educated

Although their lives and livelihoods revolved around combat, most samurai were highly educated and cultured. The Bushido code that the samurai followed emphasised lifelong self-betterment, and samurai warriors were usually exceptionally literate and proficient at maths and science. They were also greatly interested in the arts, and often pursued hobbies like painting and, somewhat surprisingly, flower arranging.

Foreigners could become samurai

Although it was extremely uncommon, it was possible for people of non-Japanese ancestry to became members of the samurai class. The first foreigner to join the samurai was an African warrior known only as Yasuke, and he fought for the Japanese lord Oda Nobunaga during the ‘Warring States’ period. At least three Europeans are also known to have attained samurai status.

Disgraced samurai could regain their honour through suicide

For a samurai, bringing dishonour to oneself was a fate worse than death. If a samurai warrior had violated the Bushido code, he could regain his honour through an act of ritualistic suicide known as seppuku. To commit seppuku, a kneeling samurai would use a sharp blade to disembowel themself, before a trusted friend, known as their ‘second,’ would decapitate them with a katana.

Women had to pay samurai to marry them

Marriage to a samurai was an easy way for lower class women in Japanese society to gain social prestige. The samurai were well aware of this, and they took advantage by making women who wanted to marry them pay for the privilege. The fees could be steep, and families often scraped together their savings to cough up the funds for their daughter.

They were known as Bushi in Japan

Although these days the word ‘samurai’ is used to refer to individual warriors of the samurai caste, in Japan they were actually referred to as ‘bushi,’ which roughly translates to ‘a person whose primary occupation is combat.’ The term ‘samurai’ was only used to refer to the entire social class that these warriors belonged to.

They were seen as defenders of Japan

Although they generally fought for Japanese lords who paid them handsomely, the samurai were seen by the wider population as the defenders of Japan from hostile tribes and nations. This probably explains why the samurai were so revered, and why they enjoyed such an elevated social status in Japanese society.

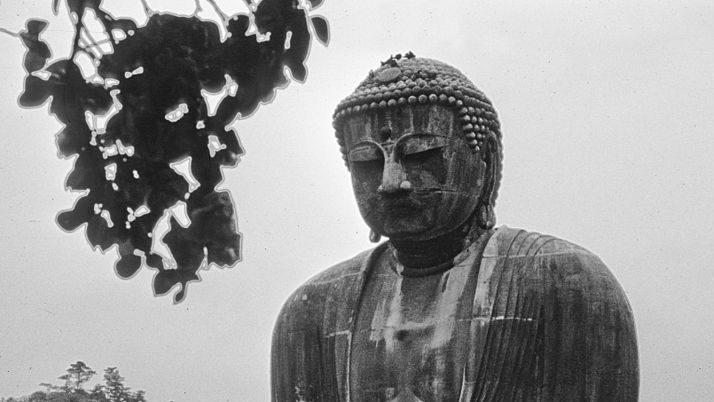

The samurai were influenced by Zen Buddhism

From the 13th century onwards, the samurai became highly influenced by the teachings of Zen Buddhism. Meditation became a core part of samurai training, helping warriors remain calm and collected in the face of death and freeing their minds from distraction, allowing them to channel all of their focus during combat.

They embraced tea ceremonies

Tea has long held an incredibly important place in Japanese culture, and one of the practices that the samurai adopted from Zen Buddhism was the tea ceremony. A highly elaborate ritual steeped in tradition, tea ceremonies involve preparing, serving and drinking tea in a very particular way, and they blend meditation with more performative elements.

Many samurai became journalists

After the Maeji Restoration outlawed the samurai class, the warriors were left without a source of income. While some joined the military or police, others decided to make use of the literary skills that samurai were famed for, and large numbers of former warriors became journalists and newspaper reporters.

Dragonflies were a symbol of the samurai

Samurai armour and weaponry was often adorned with dragonfly motifs, and the insect was strongly associated with the warrior class in Japanese culture. Dragonflies are voracious predators incapable of flying backwards, reflecting the way samurai warriors would never back down or retreat in the face of danger.

The samurai wore their hair in top knots

Long before top knots became a symbol of the hipster movement, the hairstyle was worn by samurai warriors. After shaving the sides of their heads, samurai would tie the hair on the top of their head into a tight bun which helped keep their helmet firmly on during combat.

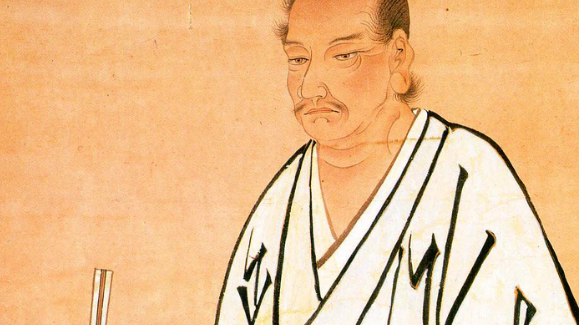

Miyamoto Musashi was the most dangerous samurai

Miyamoto Musashi was a revered samurai, widely believed to be the best duellist of all time. Throughout his life, Musashi fought and won at least 61 duels to the death, with many of Japan’s greatest warriors seeking him out to test their skills. In addition to his combat prowess, Musashi was also an accomplished poet, writer and artist.

Large scale suicide had to be outlawed

It wasn’t uncommon for a samurai to commit suicide when their master died, and the death of a powerful lord would frequently result in the mass suicides of all of the samurai that served him. Known as ‘junshi,’ these mass suicides caused so much damage to the samurai class that they were eventually outlawed, although that had little effect on the practice.

The samurai may have descended from a marginalised minority

The Ainu people were an ethnic group in Japan who experienced widespread discrimination for hundreds of years. Due to the fact that many samurai shared physical characteristics with the Ainu, it has been hypothesised that the group eventually formed the samurai class, reversing their position in the social hierarchy to become one of the most powerful castes in Japanese society.

Masterless samurai were known as Ronin

Traditionally, when a samurai’s master died, they either killed themselves or found a new lord to serve. Over time, however, a growing number of samurai chose to remain masterless, generally working either as sell-swords or bodyguards. Many of the most famous samurai, such as the legendary Miyamoto Musashi, were Ronin.

Samurai clans fought each other for power

As the samurai class became more formally defined, groups of samurai warriors formed into clans. Two of the largest clans were the Minamoto and Taira, with tens of thousands of members between them. It wasn’t unusual for samurai clans to go to war with each other, vying for control of various regions.

The Kabukimono were an unruly offshoot of the Ronin

Like the Ronin, the Kabukimono were masterless samurai who played by their own rules. Unlike the Ronin, however, who still embodied many samurai values, the Kabukimono dressed flamboyantly and generally sowed chaos wherever they went, murdering innocent civilians and organising violent street fights with each other.

They refused to reintegrate into society

After the samurai class was abolished, samurai warriors were expected to take normal jobs and reintegrate into society. Many refused, however, believing civilian life to be dishonourable and beneath them. These samurai attempted to keep their way of life alive, working as swords for hire, but ultimately they were rendered obsolete by advancements in firearms.

Being a samurai’s wife was hard work

Samurais’ wives were expected to be entirely obedient and subservient, catering to their husbands’ every whim and wish. As if that wasn’t bad enough, samurai warriors also reserved the right to keep as many mistresses as they wanted, a privilege which was completely unavailable for their wives.

Samurai warriors had sex with teenage boys

Experienced samurai generally took on teenage apprentices, and, thanks to the perks of belonging to an aristocratic warrior class, there was no shortage of applicants. Things got pretty creepy, however, thanks to a law that allowed samurai to have sex with their teenage apprentices, although consent was notionally required.

The Yakuza may have descended from Samurai

The Yakuza is one of the world’s largest criminal enterprises, with an estimated yearly revenue of $13 billion. While the organisation’s origins are murky, it is widely theorised that they descended from the Ronin. According to this theory, individual Ronin started banding together for protection during the Edo period, eventually taking over the underground gambling industry and becoming the first members of the Yakuza.

They used to shoot dogs for practice

The samurai made extensive use of longbows, and they practised diligently. One of their favoured methods of training was called ‘inoumono,’ and it basically consisted of hunting down dogs on horseback and slaughtering them with arrows. Sometimes, padded arrows were used so that targets could be reused, but most of the time the samurai shot to kill.

Samurai’s wives could be expected to kill themselves

Seppuku, the ritualistic form of suicide which disgraced samurais could use to regain their honour, is one of the most well-documented aspects of samurai culture. What’s less widely known is that the wives of disgraced warriors were expected to commit suicide alongside their husbands, albeit in a slightly different version of the ritual that involved slitting the throat instead of disembowelment.

The samurai became diplomats and statesmen

The Edo Period was a time of relative peace in Japan, and the reigning Tokugawa shogunate sought to unite the country. Without much fighting to occupy them, many samurai began working as bureaucrats, diplomats and statesmen, although they continued to carry their katanas to denote their status.

They used guns

The samurai are often regarded as the most skilled warriors in history, and most depictions of them focus on their sword-fighting expertise. However, from the 15th century onwards, samurai warriors also made use of firearms such as matchlock pistols and muskets. Many samurai even had specialised firearms, known as ‘Samurai-zutsu,’ custom built for them.

They defended Japan from the Mongols

Between 1274 and 1281, Kublai Khan of the Mongol-led Yuan Dynasty launched multiple invasions of Japan, seeking to add it to his list of vanquished nations. These conquests ultimately failed as a result of fierce resistance by the samurai, who proved more than a match for the Mongol warriors. Numerous new weapons were invented as a result of the conflict, including the first hand grenades.

The sons of samurai were trained from a young age

The sons of samurai were expected to follow in their father’s footsteps, and their combat training began at a young age. It was rare, however, for a samurai to train his own children. Instead, they would be sent to live with instructors who would train them in everything from warcraft to tea ceremonies.

Samurai regarded ninjas as dishonourable

Emerging during the 15th century, ninjas were ruthless mercenaries and assassins who sold their services to the highest bidder. The ninja’s clandestine methods – which heavily emphasised the use of stealth and deception – earned them the scorn of the samurai, who viewed them as dishonourable, cowardly and amoral. Despite this, they still regularly hired ninjas when they didn’t want to get their own hands dirty.

They used clubs

Most people imagine the samurai as incredibly skilful warriors, wielding their katanas with extraordinary precision. While they certainly were deadly with a sword, they also employed more crude methods. The kanabō was a short wooden club studded with metal spikes, and it was often a samurai’s favoured choice of weapon in real combat.

They could be ordered to commit seppuku for failing in their mission

On March 24th, 1860, Ii Naosuke, Chief Minister of the Tokugawa shogunate, was assassinated by a group of 17 Ronin outside the gates of the Edo Castle. Afterwards, it was determined that the samurai guarding Ii had not done enough to protect him. While the guards who were severely wounded had their pay reduced, those with only minor injuries were ordered to commit seppuku.

They held drinking contests

Samurai figured out ways to turn pretty much everything into a competition, including alcohol consumption. Sake drinking contests were highly ritualised events following strict rules, and warriors were expected to be able to hold their liquor. Falling ill or otherwise losing control was seen as dishonourable and weak, while remaining stoic and collected after ingesting copious amounts of booze was considered admirable.

Some samurai were masters of guerrilla warfare

While many samurai employed a bit of deception from time to time, Kusunoki Masashige was a straight up master of guerrilla warfare. Amongst his other tactics, Kusunoki frequently employed ambushes, night raids, booby traps and psychological warfare, and he used dummy warriors to lure his enemies into the open. Despite this, Kusunoki has gone down in history as the very embodiment of the Bushido code.

The samurai were most active during the Sengoku period

Lasting from 1467 to 1567, Japan’s Sengoku period was marked by near-constant civil war, social unrest and political intrigue. It is also the time when the samurai were most active, with many legendary battles regularly taking place as various lords and clans fought bitterly to rule over the country.

It wasn’t unusual for samurai to abandon their lords

Loyalty to one’s lord was one of the fundamental pillars of samurai culture, but in practice this loyalty was conditional. The relationship between a lord and his samurai was very much reciprocal, and if a lord failed to live up to his side of the bargain – for example by failing to bestow wealth and prestige upon his warriors – they would abandon him in an instant.

A samurai would first go into battle at the age of 15

The children of samurai were expected to join their fathers in combat, and they would often take part in their first battle at the age of 15. A particularly precocious warrior might fight at an even younger age, such as Uesugi Kenshin, a samurai of great renown who first tasted battle at the age of 13 during the Echigo Civil War.

Samurai swords were brittle

The katana is perhaps the most legendary weapon of all time, and most people assume that they were forged by master craftsmen to be nigh-on indestructible. In reality, while incredibly sharp and perfect for slashing through flesh, katanas were also quite brittle, and prone to shattering if used against armour.

A samurai’s title could be revoked after death

The title of samurai carried great prestige, and it could be revoked after death. This would often occur when a samurai had broken the Bushido code and died dishonourably, or if he had failed in his duties. Sometimes, disgraced samurai would be allowed to keep their title if they committed seppuku with exceptional bravery and dignity.

Samurai passed down their armour

After a samurai died, his armour would be passed down to be used in combat by one of his children, generally his eldest son. Since samurai often died in battle, repairs would normally be required before the armour could be re-used. If he had no children to inherit his belongings, a samurai warrior would be buried in his armour with his sword by his side.

They could fight with war fans

Tessenjutsu is a martial art that involves the use of Japanese war fans. These resembled normal, foldable hand fans, but were made out of solid iron and possessed a lethal, razor-sharp edge. While they were rarely used on the battlefield, samurai warriors still often trained in Tessenjutsu and carried war fans as a weapon of last resort.

The samurai were influenced by Shintoism

Shintoism is the oldest religion in Japan, dating back to at least 300 BC. Followers of Shinto worship beings known as Kami, spirits closely linked with nature. Although Buddhism had become the dominant religion with Japan’s nobles by the time of the samurai, they still drew heavily on Shintoism, using its principles to design the code of ethics that would eventually become known as Bushido.

It was an honour for a samurai to enter battle first

The samurai lived to display their fearlessness in combat, and it was seen as a great honour to be the first warrior to enter a battle. This changed in the Sengoku period with the introduction of firearms, which made frontal charges more suicidal than valiant. The samurai then changed their tactics, allowing more disposable soldiers to form the front line and entering the fray last.

They sometimes worked as assassins

Although samurai portrayed themselves as honourable warriors, they would occasionally work as assassins, particularly if they were masterless. As well as killing for money, samurai would also carry out assassinations to further their own political goals or if they genuinely believed killing their target would benefit the greater good.

They used throwing stars

Shurikens – more commonly known as throwing stars – are as synonymous with ninjas as katanas are with samurai. There is evidence that, despite viewing ninjas as dishonourable, the samurai adopted a number of their weapons, including shurikens. These would never be employed in one on one duels, however, and would be reserved for use against opponents in large-scale battles.

They were capable swimmers

In addition to proficiency with weapons and hand-to-hand combat, samurai were expected to be proficient swimmers. During the Sengoku period – throughout which the samurai were almost constantly involved in wars – they developed Suijutsu, a style of combative swimming designed to be used if they were thrown overboard during a naval engagement. As part of Suijutsu, samurai practiced swimming while wearing full armour.

They practiced breath-work

Recent studies have shown that controlled patterns of breathing can have profound affects on the nervous system, helping us remain calm in the face of extreme danger. The samurai figured this out hundreds of years ago, practicing a type of breath-work they called “Okinaga breathing,” which emphasised controlled inhalations through the nose and long exhalations through the mouth, enabling them to stay focussed during combat.

Bushido went out the window on the battlefield

While the concept of Bushido has long been romanticised, not least by governments looking to inspire fearlessness in their soldiers, studies of historical accounts suggest that the samurai rarely lived up to their own ideals on the battlefield. While samurai fought with honour in duels with other samurai, in regular conflicts they were just as likely to use vicious, underhanded tactics as any other soldier.

They sometimes killed their own lords

One of the fundamental principles of the Bushido code was unshakeable loyalty, with samurai expected to unquestioningly lay down their lives for their lords. Not all samurai abided by this, however. Betrayals weren’t all that uncommon, with Akechi Mitsuhide – a distinguished samurai general who turned on his lord and forced him to commit seppuku – providing the most infamous historical example.

Duels were rarely lethal

One of the most enduring myths about samurai is that they frequently engaged in one-on-one duels to the death, just to see who was the more skilful warrior. In reality, duels were almost always fought using wooden training weapons or unarmed entirely. That said, some Ronin, like the legendary Miyamoto Musashi, really did engage in duels using lethal force.

They spat needles at their opponents

Another technique that the samurai borrowed from ninjas was Fukumibarijutsu, otherwise known as the Japanese art of needle spitting. These needles could be fired from a blowpipe at considerable range, or spat directly from the mouth during close combat. In either case, the results were rarely fatal, but they could inflict significant pain, allowing the samurai to gain the upper hand.

Samurai armour changed over time

Warfare changed dramatically throughout the samurai’s existence, and their weapons and armour changed with it. Early samurai favoured armour made from leather, which was lighter and allowed for increased range of motion and speed when fighting with a sword. As firearms became increasingly common throughout the 16th century, samurai warriors began wearing heavier armour that incorporated iron plates.

They used a variety of combat formations

While samurai are often depicted as fighting alone, in reality they usually fought as part of an army. As such, combat formations were very important. There were at least seven distinct formations employed by the samurai, each designed for a different situation. For example, Saku (lock) was used for defensive situations, while Kakuyoku (wings of a crane) was used to try and encircle the enemy.

The kusarigama was a particularly savage weapon

One of the most vicious weapons in the samurai arsenal was the kusarigama, which consisted of a handle with a sickle blade attached to one end and a chain to the other. During combat, the chain would be swept in a wide arc, inflicting devastating wounds. The samurai would then move in and deliver the fatal blow with the sickle, usually aiming for the throat.

The samurai fired special arrows to summon spirits

Before firearms became common, samurai would begin a battle by firing a volley of arrows with bulbed heads, which would make a buzzing sound as they flew through the air. This was intended to summon Shinto spirits known as Kami, so that the beings could bear witness to the displays of valour which were about to take place.

Katanas during the Edo period were designed for lightness

The way katanas were crafted changed over time. During the Mongol invasions, new crafting techniques made the blades sturdier and more effective at piercing armour. During the Edo period, katanas were made with a single factor in mind: lightness. This was for the simple reason that by this point the samurai were working as government officials, and their swords had become purely symbolic.

Some samurai became Buddhist monks

As Zen Buddhism became increasingly influential with the samurai, they began to realise that their way of life was at odds with the principles of Karma and reincarnation. This led many samurai to stop torturing their enemies and killing innocents, while others abandoned the samurai way of life altogether and became Buddhist monks.